NY Night Train Soul Clap & Dance-Off Top 500 (421-440): Track by Track

The fourth installment, numbers 421-440, of my Soul Clap and Dance-Off Top 500 list where I count down my favorite original 45s from the Soul Clap & Dance-Off party. This page is both a track list and detailed supplementary liner notes of sorts to my Soundcloud mix/podcast. Since the mix finds the records pitched, cut, and yelled over the way I do it at my parties, this page and its YouTube playlist give you a chance to hear the original vinyl in its natural state and will hopefully also prove to be a solid resource for learning more about the records and the artists. I’ve also provided links to where you can get more in-depth in your soul journey. And the photos are clickable if you want a better view… Thanks for stopping by!

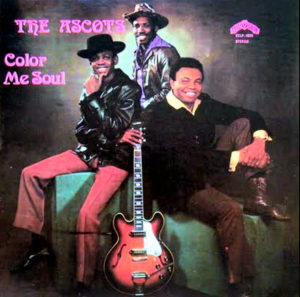

421. James Duhon “Grave Yard Creep” (Jetstream, ?) A graveyard smash straight outta east Texas’ industrial Golden Triangle I picked up from personal hero Billy Miller (RIP) of Norton Records. The uncredited band here is Port Arthur’s The Ascots (sometimes billed as The Escotts) on the prolific and crazy Crazy Cajun Huey Meaux’s Jetstream imprint. Each side of this single is credited to the song’s vocalist instead of the band. So James Duhon does this side and Talmadge Armstrong’s “Color Me Soul” is the B-Side. Also Al Trahan whose “Can I Feel” it on Spindletop is also a regular Soul Clap and Dance-Off spin, was a member of this formidable funky aggregation. Both of these sides also later appeared on The Ascots’ 1978 LP “Color Me Soul.”

A graveyard smash straight outta east Texas’ industrial Golden Triangle I picked up from personal hero Billy Miller (RIP) of Norton Records. The uncredited band here is Port Arthur’s The Ascots (sometimes billed as The Escotts) on the prolific and crazy Crazy Cajun Huey Meaux’s Jetstream imprint. Each side of this single is credited to the song’s vocalist instead of the band. So James Duhon does this side and Talmadge Armstrong’s “Color Me Soul” is the B-Side. Also Al Trahan whose “Can I Feel” it on Spindletop is also a regular Soul Clap and Dance-Off spin, was a member of this formidable funky aggregation. Both of these sides also later appeared on The Ascots’ 1978 LP “Color Me Soul.”

While Meaux had a number of hit productions, and was regarded nationally as the promotions man big labels needed to break a record in the Houston/east Texas markets, he didn’t do a whole lot to call attention to his own roster of deserving newcomers like The Ascots and this release is one of many that appeared long after they were recorded. In his invaluable Houston music resource on “Bayou City Soul,” Brett Koshkin explains:

In the late seventies, Meaux facing a slew of tax related issues, sought to defray his bills by releasng a then unprecedented amount of unreleased material he had recorded through the years. The tax scam album as it is today known was the shady art of recording and then releasing a record for the sole purpose of claiming it at an inflated cost of production and loss come April 15th. A method for making gargantuan tax write-offs without having actually spent said costs by a long shot. It was incredibly illegal but not the easiest manner in which to be caught for tax evasion. Of the thousands of albums manufactured, The Ascots were one of the more quality related releases that sadly, were destined for the dumpster instead of record store shelves.

– Check out Brett Koshkin’s excellent Bayou City soul page about the Ascots and this record

422. Gene “Bowlegs” Miller “Frankenstein Walk” (Hi, 1969)

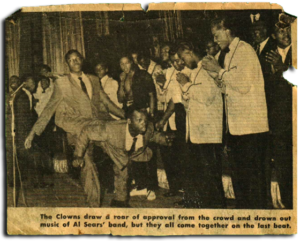

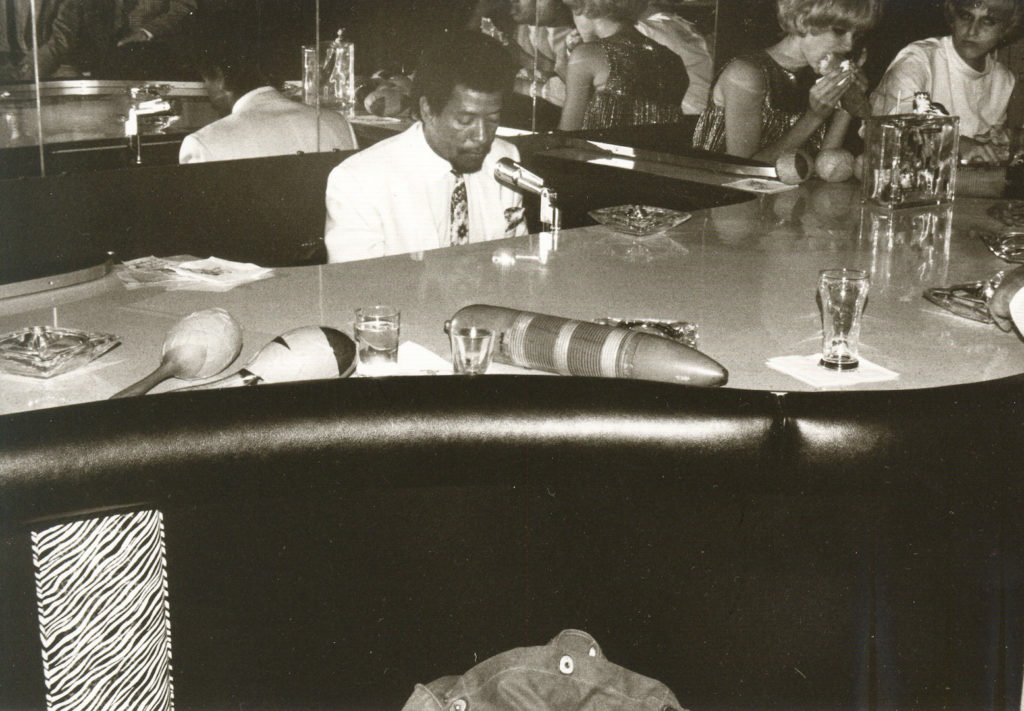

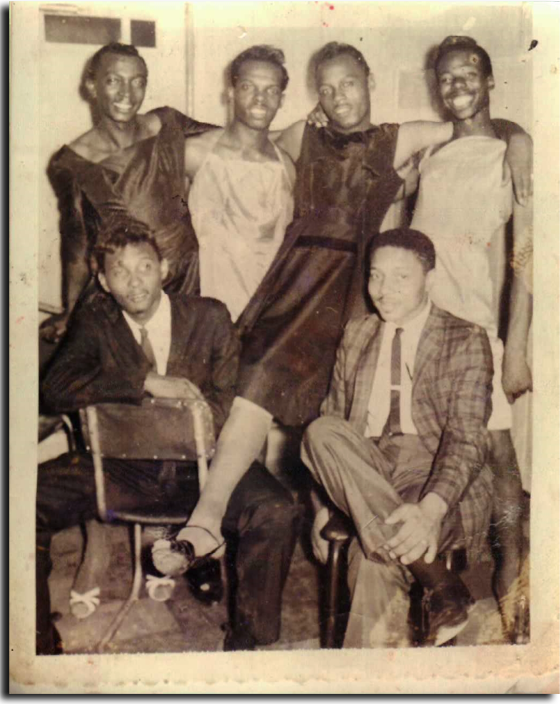

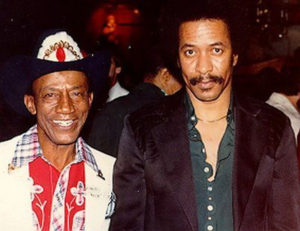

A dance I make everybody do every Halloween and sometimes off season! Just follow Bowlegs’ easy instructions and you’ll be doin’ it in no time! “Frankenstein Walk” isn’t just a novelty but also hard-hitting Hi-Records’ Memphis soul at its funkiest! Bandleader/session player/producer/songwriter/arranger Gene “Bowlegs” Miller was a key figure in the evolution of the timeless and internationally adored Memphis sound. After cutting his teeth as a sideman with the likes of Tuff Green and Phineas Newborn, Sr., Miller started his own combo, became a popular bandleader all over Beale Street and beyond, and cut a few of his own records for the Vee-Jay, Zab, and Christie imprints. The historical moment when young Booker T Jones of Booker T and the MG’s fame switched from bass to organ was as a member of Bowlegs’ band at their Flamingo Club residency. At the recommendation of The Ovations, he got in early on the phenomenon that was Goldwax Records who released his smokin’ instrumental double-siders “Bow-Legged”/”Toddlin” and “Here It Is Now”/”What Time Ye Got.” After establishing himself as a regular addition to The Memphis Horns, and contributing his serious trumpet skills to a number of iconic Stax sides by the likes of Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, and Don Covay, Bowlegs was one of the Memphis musicians imported to Fame Studios in 1966 to become an integral part of the Muscle Shoals Horns – both as a musician and arranger on standards like Etta James “Tell Mama” and Clarence Carter’s “Slip Away.” Returning to Memphis just in time to play a vital role in the golden age of Hi Records, Bowlegs wasn’t only the featured artist on tracks like this one, but was also involved as a musician, arranger, writer, and/or producer on a number of the label’s classic sessions. He’s also credited with helping discover a number of significant artists from Ann Peebles to Peabo Bryson. He spent the remainder of his life in deeply involved in the music industry from funk to Hip Hop and beyond – producing and arranging for the likes of Denise LaSalle, Ann Sexton, and Ollie Nightingale, and helping break the likes of Sugar Hill Gang and LL Cool J as an independent radio promotions man. A mere paragraph can’t do justice to Gene Miller and his decades of accomplishments.

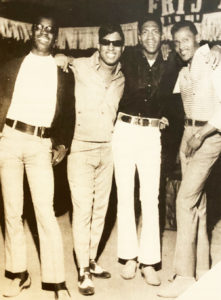

Gene “Bowlegs” Miller, Billy Foster, Etta James, and Rick Hall at Fame Studios in 1967

– Check out this lovingly written Bowlegs Miller post from Red Kelly

Other Gene “Bowlegs” Miller original 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off:

– Bow-Legged (Goldwax, 1964)

– Toddlin’ (Goldwax, 1964)

– Here It Is Now (Goldwax, 1966)

– What Time Ye Go (Goldwax, 1966)

423. Clea Bradford “My Love’s A Monster” (Cadet, 1968) While this track was a bit too slick for the raw sound of my earliest parties, and only appeared on Halloween, I began dusting it off with more frequency in my soul sets as I was gradually seduced over the years by the creativity, dynamics, and musicality of Clea Bradford and these jazz players taking a soul turn. Since some jazz heads dismiss their heroes’ soul and pop deviations as dumbing down or selling out, and the aesthetics aren’t always an easy fit with much of the soul spectrum’s preferences, tracks are often passed over completely. But, seeking a diversity of sound within my genre sets, and someone who’d always rather create a home for a misfit track than more predictable choices buoyed by the safety of subcultural consensus, I’m sad I didn’t see the true beauty of this fiery ember when I picked it up over a decade ago. And its so punchy and unique I still don’t fully understand why my rough aesthetic was so unbendable back then! And listen to those cool guitar runs and the massive drum break!

While this track was a bit too slick for the raw sound of my earliest parties, and only appeared on Halloween, I began dusting it off with more frequency in my soul sets as I was gradually seduced over the years by the creativity, dynamics, and musicality of Clea Bradford and these jazz players taking a soul turn. Since some jazz heads dismiss their heroes’ soul and pop deviations as dumbing down or selling out, and the aesthetics aren’t always an easy fit with much of the soul spectrum’s preferences, tracks are often passed over completely. But, seeking a diversity of sound within my genre sets, and someone who’d always rather create a home for a misfit track than more predictable choices buoyed by the safety of subcultural consensus, I’m sad I didn’t see the true beauty of this fiery ember when I picked it up over a decade ago. And its so punchy and unique I still don’t fully understand why my rough aesthetic was so unbendable back then! And listen to those cool guitar runs and the massive drum break!

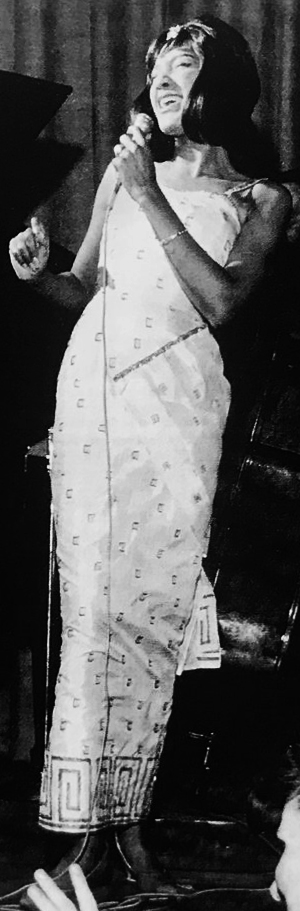

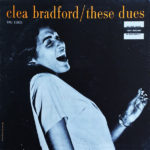

Highly regarded by jazz critics and her fellow musicians for her versatility and range, and standing 6-foot tall with long straight hair, high cheekbones, and striking features that reflected her Ethiopian/Chocktaw ancestry, Clea Bradford was as magnificent sonically as she was visually. The daughter of a preacher man, she was born in Clarksdale Mississippi, raised in Charleston, Missouri, and wound up moving to St. Louis with her mother. Recognized for her musical talent from early childhood, she performed publicly for the first time at the age of three and was soon taking part in neighborhood jam sessions at Jimmy Forrest’s house swingin’ with the likes of Miles Davis, Clark Terry, and Oliver Nelson. Can you imagine the sound of this pantheon in a living room? Or what an uncommon educational opportunity that would’ve been for a young musician? Soon a featured live vocalist with Forrest, Ike Turner, and other bands around the Gateway to the West, Bradford was already earning a living as a musician by the time she was seventeen. Before long she’d packed her bags and let music and wanderlust lead her on an epic voyage that crisscrossed a dizzying map of residences. She called New York, L.A., Chicago, D.C./Baltimore, Detroit, Cleveland, and Buffalo home at least one point in her restless career.  As a Fortune Records nut I can’t wait to one day get a chance to hear to her elusive 1958 Hi-Q debut single “I’ve Got You.” In the 60s she turned out a a pair of well-received jazz LPs featuring her legendary St. Louis friends Terry and Nelson plus all-star heavy-hitters like Hank Jones, Barry Galbraith, Osie Johnson, Milt Hinton, and George Duvivier, “These Dues” (1961 on Prestige subsidiary Tru-Sound) and “…Now” (1965 on Mainstream), before the eclectic collection from which this track emerges, “Her Point Of View” (1968 on Chess’ Cadet subsidiary). While most of the other “Her Point Of View” tracks are uniquely stylized interpretations of standards (including this single’s flip side, her killer take on “Summertime”), Bradford penned this original sexy colossus with the stellar producer/arranger Richard Evans.

As a Fortune Records nut I can’t wait to one day get a chance to hear to her elusive 1958 Hi-Q debut single “I’ve Got You.” In the 60s she turned out a a pair of well-received jazz LPs featuring her legendary St. Louis friends Terry and Nelson plus all-star heavy-hitters like Hank Jones, Barry Galbraith, Osie Johnson, Milt Hinton, and George Duvivier, “These Dues” (1961 on Prestige subsidiary Tru-Sound) and “…Now” (1965 on Mainstream), before the eclectic collection from which this track emerges, “Her Point Of View” (1968 on Chess’ Cadet subsidiary). While most of the other “Her Point Of View” tracks are uniquely stylized interpretations of standards (including this single’s flip side, her killer take on “Summertime”), Bradford penned this original sexy colossus with the stellar producer/arranger Richard Evans.

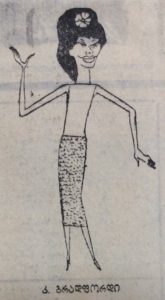

Gigla Pirtskhalava’s Bradford illustration from her USSR tour! From “Tbilisi,” July 20, 1966. See Mariami Khatiashvili’s article

.

– Check outFunky 16 Corners‘ appreciation of “My Love’s A Monster”

– Go to this Washington Post obituary for info about Clea Bradford’s life and career

read Mariami Khatiashvili’s excellent article about U.S. Cold War jazz diplomacy

424. Andre Scott “Shadow Knows” (Neely, ?)

This upbeat lo-fi soul dancer, with its howling, demonic backing vocals, and baritone sax-laden playfully sinister feel, oozes charm and feel. And for a tiny production by an unknown artist on an unknown label, its an action packed composition with a stellar vocal performance, a killer band, and some fancy horn arrangements. The only known release on Neely Records, “Shadow Knows” is also an ultra-rare obscurity shrouded in mystery. The credited publishing company on the label, Moo-Lah Pub., also appeared on a number of late ‘60s Chicago releases – with a few by the Windy City’s Lovelites, plus the Chi-Lites, Denice Chandler (Denise Williams!) and Lee Sain on Toddlin’ Town, etc. Secondly there was a 1968 record by an Andre Scott on Sidney Barnes’ Chi-town imprint Sunflower. The soulful singer on the A-Side “One Girl” sounds a whole lot like it could be the singer on “Shadow Knows” if he was shooting for tender melodic emotion rather than horror music. None of the other clues lead anywhere so I’m gonna hedge my bets that Andre Scott was a late-‘60s Chicago singer who did “One Girl” and this was an upstart label that for whatever reason never fully materialized and thus “Shadow Knows” was just a limited run of a few copies that never saw proper release.

425. Eddie Perrell “Hex” (Shurfine, 1966)

A pounding macabre masterpiece from both the Haunted Hop and the Soul Clap on Atlanta’s under-estimated Shurfine Records. Aesthetically somewhere between Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and a Creedence Clearwater Revival cover of Screeamin’ Jay Hawkins, “Hex,” with its sinister organ, overdriven bluesy guitar leads, and Perrell’s extraordinary soul screaming, is as much early hard rock as heavy soul. Mighty Hannibal’s Shurfine records from around the same time with local garage rockers St. John and The Cardinals backing him also have a dense soul rock sound and The Cardinal’s 45 appeared on the label a year before this. While this sounds like a different band here and the drums are burried, if their skin-pounder Dennis St. John happens to be on “Hex,” that would make two Atlanta Halloween favorites in two years for him as, long before his decade leading Neil Diamond’s band, his solid soulful beat drove Mike Sharpe’s original version of the classic Classics IV hit “Spooky.”

Reading Aaron Cohen’s excellent “Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power” in the beginning of quarantine I was struck by the early chapter where young Duke of Earl Gene Chandler is in the hallway of Englewood High School with Eddie Perrell practicing harmony for their group The Gay Tones. I immediately thought that there couldn’t be that many Eddie Perrells out there in the soul universe and this had to be the same singer who shouted one of my favorite Atlanta records “Hex” on Shurfine – which also had to be the cool and unusual voice with miles of style you hear over Booker T and the MG’s backing on another Soul Clap spin “The Spoiler” (I also like to turn Vigon’s French version!). While some sources (including Discogs) have them listed as different singers, my research confirms that “Hex’s” Perrell is also Eddie Purrell from the Volt single and the stone soulful “Had To Be A Lover” 45 on Chicago’s Hit Sound Records. Perrell also recorded as Little Eddie Love whose rockin’ 1960 single “Come Runnin’ To Me Baby” appeared on both L.A.’s Mack IV and Philly’s Red Top imprints. He also had a couple of small releases on Maryland’s Plum Good and the mysterious Quette Records. Plus he has two 1972 production credits on Cleveland vocal trio Sly, Slick And Wicked’s Paramount singles plus a 1973 co-production credit with James Brown on their “Sho’ Nuff” on Soul Brother No. 1’s People imprint. Chicago, L.A./Philadelphia, Atlanta, Maryland, Memphis, Cleveland, and mysterious James Brown land (NYC? Macon?)! A different city for each record! Like Clea Bradford earlier in this list, Eddie Perrell liked to ramble!

Reading Aaron Cohen’s excellent “Move On Up: Chicago Soul Music and Black Cultural Power” in the beginning of quarantine I was struck by the early chapter where young Duke of Earl Gene Chandler is in the hallway of Englewood High School with Eddie Perrell practicing harmony for their group The Gay Tones. I immediately thought that there couldn’t be that many Eddie Perrells out there in the soul universe and this had to be the same singer who shouted one of my favorite Atlanta records “Hex” on Shurfine – which also had to be the cool and unusual voice with miles of style you hear over Booker T and the MG’s backing on another Soul Clap spin “The Spoiler” (I also like to turn Vigon’s French version!). While some sources (including Discogs) have them listed as different singers, my research confirms that “Hex’s” Perrell is also Eddie Purrell from the Volt single and the stone soulful “Had To Be A Lover” 45 on Chicago’s Hit Sound Records. Perrell also recorded as Little Eddie Love whose rockin’ 1960 single “Come Runnin’ To Me Baby” appeared on both L.A.’s Mack IV and Philly’s Red Top imprints. He also had a couple of small releases on Maryland’s Plum Good and the mysterious Quette Records. Plus he has two 1972 production credits on Cleveland vocal trio Sly, Slick And Wicked’s Paramount singles plus a 1973 co-production credit with James Brown on their “Sho’ Nuff” on Soul Brother No. 1’s People imprint. Chicago, L.A./Philadelphia, Atlanta, Maryland, Memphis, Cleveland, and mysterious James Brown land (NYC? Macon?)! A different city for each record! Like Clea Bradford earlier in this list, Eddie Perrell liked to ramble! Who is this supreme soul journeyman and why was he moving around the country after each killer record? My internet sleuthing revealed that Eddy Perrell has his own web site! But it’s currently down… hmmm…. And he’s been recently active! He recorded a cool contemporary funk CD/MP3 single “Papa Was a Pistol I’m a Son of a Gun” in 2015 on the same imprint as “Yes, I Got A Chick On The Side, Sho Nuff” 45, Plum Good! So that must’ve been his own imprint? And now it appears he’s in Las Vegas. And next I found a press release for “Papa Was A Pistol.” It begins, “If you don’t know Eddie Perrell let us give you a little background so you can find out who he is…” I thought this was the moment I’d been waiting for. But the bio starts with the Gay Tones and skips right to “Sho Nuff” being sampled by Justin Timberlake and Jay Z on “Suit and Tie.” But what about the decades in between? I need to know more about this fine artiste and his mysterious ’60s sides. In the mean time I’m gonna get ready for Christmas eight month’s in advance with another recent Perrell digital single “Hey There Mama Santa” (2019).

Who is this supreme soul journeyman and why was he moving around the country after each killer record? My internet sleuthing revealed that Eddy Perrell has his own web site! But it’s currently down… hmmm…. And he’s been recently active! He recorded a cool contemporary funk CD/MP3 single “Papa Was a Pistol I’m a Son of a Gun” in 2015 on the same imprint as “Yes, I Got A Chick On The Side, Sho Nuff” 45, Plum Good! So that must’ve been his own imprint? And now it appears he’s in Las Vegas. And next I found a press release for “Papa Was A Pistol.” It begins, “If you don’t know Eddie Perrell let us give you a little background so you can find out who he is…” I thought this was the moment I’d been waiting for. But the bio starts with the Gay Tones and skips right to “Sho Nuff” being sampled by Justin Timberlake and Jay Z on “Suit and Tie.” But what about the decades in between? I need to know more about this fine artiste and his mysterious ’60s sides. In the mean time I’m gonna get ready for Christmas eight month’s in advance with another recent Perrell digital single “Hey There Mama Santa” (2019).I also found some Eddie Perrell mentions in the trade magazines. The best was this award of sorts from the May 27, 1967 edition of “Record World” that makes me think Stax/Volt probably neglected to work this Donald “Duck” Dunn / Booker T. Washington composition despite the fact that it shot up to #2 on one of the most important stations of the time, Chicago’s pioneering home of “The Cool Gent” Herb Kent, “The Blues Man” Pervis Spann, and other black radio icons WVON Chicago:

Most Unrecognized Smash of the Year: Would you believe that “The Spoiler,” Eddie Perrell, Volt, has sold 30,000 copies in Chicago and is second only to “respect” at WVON? Deejays do not want to take this record seriously. Just because they don’t “hear” the record, they won’t play it and give it a chance with the public that it deserves. Stax-Volt is dead serious, and thus far not one market, including Memphis, has even tried to confirm the fantastic Chicago action.

Eddie Perell’s official website

Other Eddie Perrell original 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off:

– The Spoiler 1967

426. Jackie Shane “Stand Up Straight And Tall” (Modern, 1967)

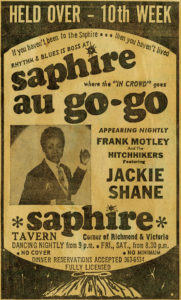

While I agree that Jackie Shane’s interpretation of William Bell’s “Any Other Way” is easily her greatest side for so many reasons, “Stand Up Straight And Tall” is my number two and, because you don’t hear it as frequently, my most regularl spin. There’s really nothing quite like this one in either Shane’s repertoire or elsewhere. This Modern Records one-off finds Shane working with new musicians, liberated from Frank Motley’s band, and gettin an opportunity to record an original composition without Juggy Murray’s overbaked production. Jackie brought the teenage organist from her mother’s church Chester Perry in to contribute the strange and beautiful hammond oscillations that dominate the backing track. Jimmy Nolan, whose high flying ’50s fretwork secured his place in history long before he invented an entirely new guitar vocabulary as James Brown’s secret weapon, contributes the subtle rhythm guitar. Rob Bowman’s brilliant liner notes to Numero Group’s comprehensive Shane collection “Any Old Way” state that the track’s writers/producers, siblings Mike James Kirkland and Bob Kirkland (Mike and the Censations, etc), were opposed to Shane’s suggestion to add a horn section. While brass could’ve made a more commercial record, I’m thrilled they were omitted and they kept this simple. While a soulful but restrained rhythm section anchoring an adventurous organ has sonic similarities to many of the soul jazz masterpieces of the era, on this track the relationship is distinct from the former in both style and economy. The emphasis on bottom end, elegance, and empty space results in an airy, eerie, and more contemporary feel. Furthermore, the minimalist approach provides Jackie Shane more room on the canvas than ever before to paint her picture.

While I agree that Jackie Shane’s interpretation of William Bell’s “Any Other Way” is easily her greatest side for so many reasons, “Stand Up Straight And Tall” is my number two and, because you don’t hear it as frequently, my most regularl spin. There’s really nothing quite like this one in either Shane’s repertoire or elsewhere. This Modern Records one-off finds Shane working with new musicians, liberated from Frank Motley’s band, and gettin an opportunity to record an original composition without Juggy Murray’s overbaked production. Jackie brought the teenage organist from her mother’s church Chester Perry in to contribute the strange and beautiful hammond oscillations that dominate the backing track. Jimmy Nolan, whose high flying ’50s fretwork secured his place in history long before he invented an entirely new guitar vocabulary as James Brown’s secret weapon, contributes the subtle rhythm guitar. Rob Bowman’s brilliant liner notes to Numero Group’s comprehensive Shane collection “Any Old Way” state that the track’s writers/producers, siblings Mike James Kirkland and Bob Kirkland (Mike and the Censations, etc), were opposed to Shane’s suggestion to add a horn section. While brass could’ve made a more commercial record, I’m thrilled they were omitted and they kept this simple. While a soulful but restrained rhythm section anchoring an adventurous organ has sonic similarities to many of the soul jazz masterpieces of the era, on this track the relationship is distinct from the former in both style and economy. The emphasis on bottom end, elegance, and empty space results in an airy, eerie, and more contemporary feel. Furthermore, the minimalist approach provides Jackie Shane more room on the canvas than ever before to paint her picture. As an out black transgender southerner Jackie Shane spent her life standing up for herself and her beliefs. And an additional fitting metaphor here, she was one of a stand-up rock’n’roll drummer long before Maureen Tucker made it was fashionable for future generations. “Stand Up Straight and Tall’s” chorus is a reoccurring theme in Jackie Shane’s loud and proud life and career. While post-war black popular music in general, with its Little Richards, Big Mama Thorntons, and Bobby Marchans, was far more tolerant of openly gay and transgender entertainers than its white counterpart, it was still far from an easy life for these artists publicly expressing their true selves. “I’m gonna stand up straight and tall / Oh I’m not gonna let you get me down babe / ‘Cause I’ve got to much on the ball.” I can see how one today’s listeners reading things at face value could see the verses “I’m a young man / gonna have myself some fun / talkin’ ’bout pretty women / gonna try to keep me some” as an attempt to mask her sexual orientation. But Jackie was uncompromisingly herself and notoriously took no B.S. from anyone. And its impossible to imagine the Kirklands succeeding, or even attempting, to make her say something she didn’t want to say. I also think its important to point out that, because of the homophobic culture within which they were forced to operate, LGBTQ singers often communicated with their listeners on heavily nuanced subtextual levels in which gender was often knowingly flipped. Jackie Shane knew exactly who she was and what she wanted to say – and was no stranger to winking word play.

As an out black transgender southerner Jackie Shane spent her life standing up for herself and her beliefs. And an additional fitting metaphor here, she was one of a stand-up rock’n’roll drummer long before Maureen Tucker made it was fashionable for future generations. “Stand Up Straight and Tall’s” chorus is a reoccurring theme in Jackie Shane’s loud and proud life and career. While post-war black popular music in general, with its Little Richards, Big Mama Thorntons, and Bobby Marchans, was far more tolerant of openly gay and transgender entertainers than its white counterpart, it was still far from an easy life for these artists publicly expressing their true selves. “I’m gonna stand up straight and tall / Oh I’m not gonna let you get me down babe / ‘Cause I’ve got to much on the ball.” I can see how one today’s listeners reading things at face value could see the verses “I’m a young man / gonna have myself some fun / talkin’ ’bout pretty women / gonna try to keep me some” as an attempt to mask her sexual orientation. But Jackie was uncompromisingly herself and notoriously took no B.S. from anyone. And its impossible to imagine the Kirklands succeeding, or even attempting, to make her say something she didn’t want to say. I also think its important to point out that, because of the homophobic culture within which they were forced to operate, LGBTQ singers often communicated with their listeners on heavily nuanced subtextual levels in which gender was often knowingly flipped. Jackie Shane knew exactly who she was and what she wanted to say – and was no stranger to winking word play. I could go on for days about Jackie Shane but I don’t have to because, for once, this is a rare opportunity to discuss an artist with more than enough amazing resources all over the net. For years people wondered, as Sonya Reynolds and Lauren Hortie’s 2014 Videofag exhibition asked, “Whatever Happened To Jackie Shane?” She was rumored to be dead. But when she resurfaced in 2017 with Numero Group’s career-spanning compilation of her work to much fanfare, the previously reclusive star opened up to do interviews and articles appeared in nearly every imaginable publication – not only answering so many lingering questions and filling in the incomplete picture she left behind, but also offering inspiration to new fans everywhere in the process. Here are a few of the most essential reads I encountered…

I could go on for days about Jackie Shane but I don’t have to because, for once, this is a rare opportunity to discuss an artist with more than enough amazing resources all over the net. For years people wondered, as Sonya Reynolds and Lauren Hortie’s 2014 Videofag exhibition asked, “Whatever Happened To Jackie Shane?” She was rumored to be dead. But when she resurfaced in 2017 with Numero Group’s career-spanning compilation of her work to much fanfare, the previously reclusive star opened up to do interviews and articles appeared in nearly every imaginable publication – not only answering so many lingering questions and filling in the incomplete picture she left behind, but also offering inspiration to new fans everywhere in the process. Here are a few of the most essential reads I encountered…-First check out the most complete resource – Rob Bowman’s in-depth biography on Numero Group’s site

– One of my favorite music writers, NOLA’s Alison Fensterstock’s rare perspective on Shane’s career from an expert in the singer’s nuanced cultural environment from NPR

– An excellent interview with Southern Cultures where Douglas Mcgowan goes with Jackie through her old photos (you gotta check ’em out!) and get’s her talking

– Another illuminating Shane interview with VICE’s Zackery Drucker where she discusses growing up trans in the south. An excellent guide to her philosophy

– Reggie Ugwu’s beautiful feature in the New York Times

– An early spark that helped stir interest in the search for Jackie Shane from 2010… Elaine Banks’ fantastic hour-long CBC Radio feature “I Got Mine : The Story of Jackie Shane”

Other original Jackie Shane 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off:

– Any Other Way (Sue, 1963)

– Sticks And Stones (Sue, 1963)

– Comin’ Down (Sue, 1963)

427. Yvonne Fair “Say Yeah Yeah” (Dade, 1963)

Have mercy! Yvonne Faire’s gotta be one of the most exciting soul shouters to ever grace this planet! And while her 1962 James Brown produced sides “I Found You,” “Tell Me Why,” and “It Hurts To Be In Love” are a holy trinity of stone cold classics and way ahead of their time, the explosion of “Say Yeah Yeah” gazes deeper into the future. In 1963, when soul music was still twisting, and its popular vanguard can be exemplified by Motown hits like “Fingertips,” “Mickey’s Monkey,” and “Heat Wave,” Yvonne’s fourth record with the James Brown band was light years beyond – making giant steps towards the development of some of the hardest funk known to (wo)mankind. When this was recorded during Yvonne Fair’s tenure as one of the first in a long prestigious line of fiery divas featured in the James Brown Revue.

Have mercy! Yvonne Faire’s gotta be one of the most exciting soul shouters to ever grace this planet! And while her 1962 James Brown produced sides “I Found You,” “Tell Me Why,” and “It Hurts To Be In Love” are a holy trinity of stone cold classics and way ahead of their time, the explosion of “Say Yeah Yeah” gazes deeper into the future. In 1963, when soul music was still twisting, and its popular vanguard can be exemplified by Motown hits like “Fingertips,” “Mickey’s Monkey,” and “Heat Wave,” Yvonne’s fourth record with the James Brown band was light years beyond – making giant steps towards the development of some of the hardest funk known to (wo)mankind. When this was recorded during Yvonne Fair’s tenure as one of the first in a long prestigious line of fiery divas featured in the James Brown Revue.While this platter is uncommon in that it doesn’t have James Brown’s name on it and its not on King like the first three Fair/Brown collaborations, you are hearing her fronting the incredible phenomenon that was James Brown’s “Live At The Apollo” era band under Mr. Dynamite’s visionary musical direction. And everybody give it up for the percussive pyrotechnics of one of Brown’s most under-rated drummers Clayton Fillyau. While its easy to understand how a drummer could get obscured by the mighty shadows of Jabo Starks, Clyde Stubblefield, et al, his work here, on “Live At The Apollo,” and other J.B. classics of the time warrants greater appreciation. Its also worth noting that Dade Records boss Henry Stone, best remembered for releasing a string of chartbusting funk and disco hits on his TK/Alston imprints in the 1970s, had a longstanding business relationship and friendship with the Godfather of Soul – helping him obtain his first recording contract with King, recording his first hit “Please Please Please,” and working together on and off into the 1970s when they went into business as Brownstone Records together. As noted in the last edition of this list, Stone also recorded and released his 1960 “(Do The) Mashed Potatoes” for Dade, erasing Brown’s distinctive vocals and replacing them with King Coleman’s to mask the identity of the band and stay out of contractual trouble with Brown/Stone’s frenemy King Records’ head honcho Syd Nathan. As with this stick of dynamite, the songwriting is credited to the same JB pseudonym “Dessie Rozier” you find on Dade’s “(Do The) Mashed Potatoes.”

Perhaps its because once again King didn’t want to record a song Brown was passionate about but they didn’t see potential in? Or they didn’t want to do a fourth Yvonne Fair record after the three commercial flops? Or, like “(Do The) Mashed Potatoes),” J.B. composed “Say Yeah Yeah” for himself but he couldn’t contractually sing his own song? Whatever the case, since James Brown was obsessed with getting credited for his amazing work, and record companies knew that his name sold records, its safe to say that his name was omitted here and the songwriting pseudonym reappeared in an attempt to avoid a sticky legal showdown.

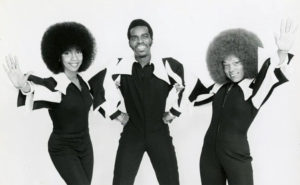

Perhaps its because once again King didn’t want to record a song Brown was passionate about but they didn’t see potential in? Or they didn’t want to do a fourth Yvonne Fair record after the three commercial flops? Or, like “(Do The) Mashed Potatoes),” J.B. composed “Say Yeah Yeah” for himself but he couldn’t contractually sing his own song? Whatever the case, since James Brown was obsessed with getting credited for his amazing work, and record companies knew that his name sold records, its safe to say that his name was omitted here and the songwriting pseudonym reappeared in an attempt to avoid a sticky legal showdown. Yvonne Fair is one of soul music’s most identifiable and electrifying voices. After getting her start in The Chantels, when the pioneering Bronx’s girl group opened for James Brown at Philadelphia’s legendary Uptown Theater in 1961, she hitched onto his Revue where she stayed on for several years a featured singer. Like so many of James Brown’s “funky divas,” the two were romantically involved and, after recording the afore-mentioned classics, in 1965 they conceived a daughter. Fair quickly moved on – marrying and giving birth to the child of another soul legend Sammy Strain, one of the few artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame twice – for both Little Anthony and The Imperials (1958-1972) and The O’Jays (1975-1992). He also cut his teeth in the immortal NYC vocal group The Chips of “Rubber Biscuit” fame!. After her killer 1966 “Just As Sure (As You Play, You Must Pay)”/”Baby Baby Baby” Smash 45 with Brown, she took some time off to devote to her young children. With her powerful Etta James-informed vocals, stunning risqué performances, and superstar persona, Fair was one of the few singers of her era who transitioned with ease into the rapid changes occurring in the musical landscape. And while it took her a minute to catch on, the ’70s saw here rise to new heights in the highly competitive soul field. Her comeback started with a spot in Chuck Jackson’s revue. After the singular voice of “Cry To Me” and a number of other hits brought her along for his ride at Motown, they laid down a few well-regarded recordings that didn’t see the light of day until the 21st Century. And though Motown didn’t see much success when they finally released one of her singles in 1970, she landed a gig as the opener on two of the Jackson 5’s whirlwind tours, hired unknown upstarts The Commodores as her backup road band, kickstarted Lionel Richie’s singing career when she had him put down his sax to duet with her, and acted in the Diana Ross star vehicle “Lady Sings The Blues.” You can get a sense of her live charisma from the nightclub scene where she sings “Shuffle Blues.” All of her years at Motown finally paid off in 1974 when she busted into the charts twice with vicious performances on a pair Norman Whitfield produced hits:

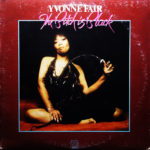

a revision of Edwin Starr’s “Funky Music Sho Nuff Turns Me On” (with an uncredited Marvin Gaye!) and an original “Walk Out The Door If You Wanna.” After a couple more screaming funky 45s, Motown released Yvonne Faire’s only LP “The Bitch Is Black.” While the album, with its suggestively-posed cover featuring Fair donning a whip, didn’t get a whole lotta stateside spins until decades later, it became an international hit with its “It Should Have Been Me” climbing up to Number 5 on the UK Pop charts. After Fair’s career wound down in the late ’70s, she retired from singing and became Dione Warwick’s wardrobe coordinator. She passed away from pancreatic cancer in Las Vegas in 1994 but her earth-shaking voice remains alive and as vital as ever on her canonical sides.

a revision of Edwin Starr’s “Funky Music Sho Nuff Turns Me On” (with an uncredited Marvin Gaye!) and an original “Walk Out The Door If You Wanna.” After a couple more screaming funky 45s, Motown released Yvonne Faire’s only LP “The Bitch Is Black.” While the album, with its suggestively-posed cover featuring Fair donning a whip, didn’t get a whole lotta stateside spins until decades later, it became an international hit with its “It Should Have Been Me” climbing up to Number 5 on the UK Pop charts. After Fair’s career wound down in the late ’70s, she retired from singing and became Dione Warwick’s wardrobe coordinator. She passed away from pancreatic cancer in Las Vegas in 1994 but her earth-shaking voice remains alive and as vital as ever on her canonical sides.– The best Fair bio I could find online is on Classic Motown

– Though I can’t find footage of Yvonne Fair from her James Brown era, you can see evidence of her unrestrained live power, sass, and showanship from this 1974 Soul Train clip of her performing “Walk Out The Door If You Wanna”

Other original Yvonne Fair 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off:

– “I Found You” (King, 1962)

– “Tell Me Why” (King, 1962)

– “It Hurts To Be In Love” (King, 1962)

– “Just As Sure (As You Play, You Must Play)” (Smash , 1966)

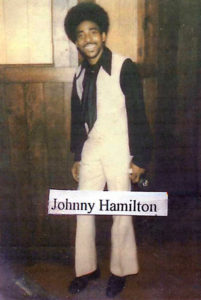

428. Little J. Hamilton “Do The Popcorn” (Soul Shack, ?)

This pummeling obscurity with the magical rhythm guitar break is the only release on Soul Shack and the only record credited to Little J Hamilton. I’m fairly certain this is Los Angeles soul singer Little Johnny Hamilton who had a couple of cool Northern soul singles on Hollywood’s odd and eclectic Dore imprint in 1966 with his band The Creators (who would go on to become world-famous funky hit-makers War!). While its difficult to determine if this is the same Little Johnny Hamilton from listening to the Dore 45s, his 1973 “Git Down” with The Soul Pack on Watts Way definitely sounds like the same singer. The only other mentions of Jack Ford Music I could locate include three Cal-Full Allstars and one Sherwood Fleming record on South-Central L.A.’s C&F label from mostly 1968. Plus this looks like an L.A. record! From the sound of things this had to be released somewhere in-between The Creators and The Soul Pack. I’d guess roughly 1969 when James Brown’s popcorn dance craze was at its height and there were dozens of smaller funky popcorn spinoffs flooding regional markets. But there’s a line that sounds like he’s saying “You see it on TV on Soul Trip.” If he’s actually saying “Soul Train” this would probably place it somewhere after the October 1971 syndication of the show. This is such an exciting performance all around, the dynamic arrangements are loaded with goodies, and its got the feeling! Not to mention this vinyl is mastered so loud and full that you can’t help but “Do The Popcorn!”

This pummeling obscurity with the magical rhythm guitar break is the only release on Soul Shack and the only record credited to Little J Hamilton. I’m fairly certain this is Los Angeles soul singer Little Johnny Hamilton who had a couple of cool Northern soul singles on Hollywood’s odd and eclectic Dore imprint in 1966 with his band The Creators (who would go on to become world-famous funky hit-makers War!). While its difficult to determine if this is the same Little Johnny Hamilton from listening to the Dore 45s, his 1973 “Git Down” with The Soul Pack on Watts Way definitely sounds like the same singer. The only other mentions of Jack Ford Music I could locate include three Cal-Full Allstars and one Sherwood Fleming record on South-Central L.A.’s C&F label from mostly 1968. Plus this looks like an L.A. record! From the sound of things this had to be released somewhere in-between The Creators and The Soul Pack. I’d guess roughly 1969 when James Brown’s popcorn dance craze was at its height and there were dozens of smaller funky popcorn spinoffs flooding regional markets. But there’s a line that sounds like he’s saying “You see it on TV on Soul Trip.” If he’s actually saying “Soul Train” this would probably place it somewhere after the October 1971 syndication of the show. This is such an exciting performance all around, the dynamic arrangements are loaded with goodies, and its got the feeling! Not to mention this vinyl is mastered so loud and full that you can’t help but “Do The Popcorn!” 429. The Fabulous Dimensions “I Can’t Take It, Baby” (Sapphire, ?)

Yet another amazing record shrouded in mystery! The two releases on Sapphire Records were by The Fabulous Dimensions and The Tenth Dymentions – who appear to be the same vocal group in two different eras. This one is of course from the soul ’60s and their “The Bushman” seems to be from the funky ’70s. Vern Ryan gets the writing credit on both and Tiny Mixtapes’ Mike Wojciechowski points out that Ryan is also associated with an oddball soul pop band called Von Ryan’s Express who had a 1971 MGM Records LP that also featured a version of “Bushman.” The labels on both indicate that Sapphire was division of the Chicago’s Sound-O-Rama Recording Inc (not to be confused with Los Angeles’ early ’60s Sound-O-Rama). The arranger here Joe Savage also got credited on a few more Chicago releases from around this same time: a couple of The Mandells on Trans World Sound, a Leontine Dupree on Nation Time, and his own Joe Savage and the Soul People on Jacklyn. But that’s all I have! I hope somebody comes out with some information about this killer diller and its soulful band.

– Mike Wojciechowski’s Tiny Mixtapes piece on The Tenth Dymensions

430. Lee Moses “Day Tripper” (Musicor, 1967)

Raw soul super-hero Lee Moses’ holy trinity of Musicor 45s kicked off in January 1967 with the only two instrumental tracks from this sextet of supreme sides, back-to-back re-imaginings of two of the day’s biggest hits, “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” and its flip “Day Tripper.” Lee Moses, in the process of establishing himself as a top-flight session guitarist, at this point had only one relatively unknown independent release featuring the prodigious vocal talents he’s best known for today. When guitarists become bandleaders they typically use their status to show off while everybody holds back. But here you find Lee Moses digging into the melody with economical authority and precision. While hammering, bending, and sliding with style and passion, and getting a few impressive licks in along the way, his guitarist/bandleader role focuses more on the band as an instrument and the effectiveness of the overall track. If anything it speaks volumes for Lee Moses’ ego that he sticks to the grid while effectively deputizing the drummer as the star of the show – bashing away at the top of the mix, establishing a dramatic intro with a break for his fireworks, and having the band lay off again later in the song for an almost hip-hop beat-focused break that elevates this dynamic arrangement.

Raw soul super-hero Lee Moses’ holy trinity of Musicor 45s kicked off in January 1967 with the only two instrumental tracks from this sextet of supreme sides, back-to-back re-imaginings of two of the day’s biggest hits, “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” and its flip “Day Tripper.” Lee Moses, in the process of establishing himself as a top-flight session guitarist, at this point had only one relatively unknown independent release featuring the prodigious vocal talents he’s best known for today. When guitarists become bandleaders they typically use their status to show off while everybody holds back. But here you find Lee Moses digging into the melody with economical authority and precision. While hammering, bending, and sliding with style and passion, and getting a few impressive licks in along the way, his guitarist/bandleader role focuses more on the band as an instrument and the effectiveness of the overall track. If anything it speaks volumes for Lee Moses’ ego that he sticks to the grid while effectively deputizing the drummer as the star of the show – bashing away at the top of the mix, establishing a dramatic intro with a break for his fireworks, and having the band lay off again later in the song for an almost hip-hop beat-focused break that elevates this dynamic arrangement. While the proliferation of ’60s Beatles covers are typically more miss than hit, the riff, rhythm, and melody of “Day Tripper” lends itself well to soul interpretation. While I’ve turned The Vontastics, J.J. Barnes, and Otis Redding’s versions at least every now and then over the years, Lee Moses’ take is the gold standard. I love both sides of this record because of the rough yet musical aesthetic, the heavy groove of the band, and the action-packed arrangements. And while I’m not always a big fan of styrene pressings, this one serves its purpose and is mastered so it feels like someone’s flailing away at the drums a few feet from your head. And while the lo-fi sound in some ways insures that this won’t feel like another insipid Beatles cover, “Day Tripper” says a lot for this bands artistry that they can pull this off with such power and distinction. I wish it was always true that its the singer not the song, but sometimes a the right song choice for the wrong band can’t even be saved by the best of ’em. I’m starting to think Lee Moses could’ve even made “I’m Henry VIII, I Am” into a beautiful thing.

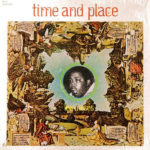

Born in Atlanta in 1941, Lee Moses achieved local prominence shining in one of many bands christened The Showstoppers. He rapidly became one of the most sought-after guitarists in A-Town’s buzzing recording scene. By the mid-’60s he took a stab at moving on up to the next level in New York City where a friend from back home, storied producer and music biz operator Johnny Brantly, got Moses session work and deals for his own solo recordings. His 1965 solo debut on Lee John, a killer stab at Joe Simon’s “My Adorable One” backed with a personal favorite “Diana (From N.Y.C.),” fell on deaf ears. In 1967 he returned to the studio to churn out a trio of landmark singles for Musicor Records: the aforementioned bangin’ instrumental covers “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” / “Day Tripper,” “Bad Girl,” and “I’m Sad About It.” These universally adored soul classics were dead on arrival in their time. After dusting himself off and getting back in the race with 1968’s strong “Never In My Life” on Dynamo, 1970’s “Time and Place” on Front Page and 1971’s legendary “Got That Will” on Maple set the stage for Moses’ big break, his first and only LP, “Time and Place.” After the album’s anticlimactic commercial performance he returned home to Georgia disenchanted with the music industry. You hear his exciting guitar work on his old friend King Hannibal’s (Mighty Hannibal!) canonical 1973 LP “Truth” (which kicks off with a version of Moses’ “Got That Will”). He revisited “Bad Girl” as “She’s A Bad Girl” and delivered a hair-raising rendition of “Dark End Of The Street” for Atlanta’s tiny Gates imprint in 1973 before disappearing into obscurity and dying of lung cancer in 1998.

Born in Atlanta in 1941, Lee Moses achieved local prominence shining in one of many bands christened The Showstoppers. He rapidly became one of the most sought-after guitarists in A-Town’s buzzing recording scene. By the mid-’60s he took a stab at moving on up to the next level in New York City where a friend from back home, storied producer and music biz operator Johnny Brantly, got Moses session work and deals for his own solo recordings. His 1965 solo debut on Lee John, a killer stab at Joe Simon’s “My Adorable One” backed with a personal favorite “Diana (From N.Y.C.),” fell on deaf ears. In 1967 he returned to the studio to churn out a trio of landmark singles for Musicor Records: the aforementioned bangin’ instrumental covers “Reach Out, I’ll Be There” / “Day Tripper,” “Bad Girl,” and “I’m Sad About It.” These universally adored soul classics were dead on arrival in their time. After dusting himself off and getting back in the race with 1968’s strong “Never In My Life” on Dynamo, 1970’s “Time and Place” on Front Page and 1971’s legendary “Got That Will” on Maple set the stage for Moses’ big break, his first and only LP, “Time and Place.” After the album’s anticlimactic commercial performance he returned home to Georgia disenchanted with the music industry. You hear his exciting guitar work on his old friend King Hannibal’s (Mighty Hannibal!) canonical 1973 LP “Truth” (which kicks off with a version of Moses’ “Got That Will”). He revisited “Bad Girl” as “She’s A Bad Girl” and delivered a hair-raising rendition of “Dark End Of The Street” for Atlanta’s tiny Gates imprint in 1973 before disappearing into obscurity and dying of lung cancer in 1998. While it took a while due to the rarity of his records, Lee Moses has achieved posthumous 21st Century soul stardom through years of the growing appreciation of DJs, collectors, and later bloggers – but it was Light In The Attic’s excellent reissues that made all of his vinyl and a few previously unreleased tracks easily accessible to all – beautifully mastered and packaged…

-Light in the Attic’s Lee Moses Page

– Sir Shambling’s Lee Moses page

– In Dangerous Rhythm’s Lee Moses page

Other original Lee Moses 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap & Dance-Off

– Diana (From N.Y.C.) (Lee John, 1965)

– Reach Out, I’ll Be There (Musicor, 1967)

– Bad Girl, Part 1 (Musicor, 1967)

– I’m Sad About It (Musicor, 1967)

– Never In My Life (Dynamo, 1968)

– Lee Moses “Got That Will” (Maple, 1970)

– Time And Place (Front Page, 1971)

– She’s A Bad Girl (Gates, 1973)

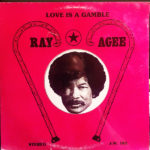

431. Ray Agee and Wilbur Reynolds Orch. “Real Real Love” (Krafton, 1967)

A relentless pounder that’s an anomaly in Ray Agee’s vast and varied catalogue blues ballads and more nuanced sophisticated movers, “Real Real Love” finds Agee’s rawest and most aggressive vocal delivery on record. The chugging bass-heavy one-chord dance groove, punctuated by the horn section’s bursts of harmony, backup singer responses, and blues guitar soloing, gives the track a more contemporary dance music feel than his other sides and also offers Agee, unconstrained by melody, a static structure to build around and offer one of his female singers a verse in hair-raising falsetto. “Real Real Love” initially appeared on Krafton under the title “Love? It’s Got To Be Real, Part 2” on the B-Side of little-known but very similar Part 1. The fourteen singles and one LP on Krafton Records are exclusively devoted to the release of Agee’s material so I imagine this is his own imprint.

A relentless pounder that’s an anomaly in Ray Agee’s vast and varied catalogue blues ballads and more nuanced sophisticated movers, “Real Real Love” finds Agee’s rawest and most aggressive vocal delivery on record. The chugging bass-heavy one-chord dance groove, punctuated by the horn section’s bursts of harmony, backup singer responses, and blues guitar soloing, gives the track a more contemporary dance music feel than his other sides and also offers Agee, unconstrained by melody, a static structure to build around and offer one of his female singers a verse in hair-raising falsetto. “Real Real Love” initially appeared on Krafton under the title “Love? It’s Got To Be Real, Part 2” on the B-Side of little-known but very similar Part 1. The fourteen singles and one LP on Krafton Records are exclusively devoted to the release of Agee’s material so I imagine this is his own imprint. Though Ray Agee isn’t well-known today, his dozens upon dozens of releases from the 1950s to 1970s make him one of rhythm and blues’ all-time most prolific artists. Crippled by polio from the age of four, Agee transcended his disability to become one of the biggest fish in the deep post-war Los Angeles R&B pond. Born the eighth of seventeen siblings in Dixon Mills, Alabama, he moved out west with his family in the 1930s and performed at local churches with his brothers in gospel group the Agee Brothers. He transitioned into the secular realm and cut his first record, the Charles Brown-style uptown blues single “Can’t Find My Way,” in 1952 and never looked back. While he made a number of quality ’50s sides, he really came into his own in the 1960s, specializing in both a deep quivery dramatic slow blues delivery and a more fluid Bobby Blue Bland-informed croon. His songwriting also deserves a mention. In addition to penning most of his own material, he wrote a number of stand-out sides for other artists including a few of my personal favorites like Johnny Guitar Watson’s Soul Clapper “I Say I Love You,” one of Bobby Blue Bland’s greatest achievements the creeping emotion of the stunning “Two Steps From The Blues” closer “I’ve Been Wrong So Long,” and Vernon And Jewel’s screaming R&B duet “It Hit Me Where It Hurts.” His prodigious output ground to a halt in the ’70s and he passed away in 1989 but his music has been made available again and again over the years on an array of various artists compilations and a handful dedicated exclusively to his work. Also since Northern Soul rarity “I’m Losing Again” became so in demand that a copy now fetches thousands of dollars, its been bootlegged a couple of times in recent years.

Wilbur Reynolds, who you find leading the band and blowing the sax on a few of Agee’s Krafton releases, was a fixture in L.A. recording scene for a couple of decades. He and his brother Jason Reynolds formed the aptly-named The Rocking Brothers and delivered three scorching singles that include iconic sides like wild “Night Train”-informed mambo-rocker “Rock It” and the jumpy “Playboy Hop.” He also went on to release a few exquisitely cooking later soul workouts that are definitely worth a turn: the B3-crazy rendering of Sam and Dave’s “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “Who’ll Cry (In Love Affair),” and, in an atypical reversal, its instrumental version A-side “Sweet’n,” the kinetic quirky “Tenderizer,” and the feel-good mid-tempo shaker where he blows his top “Huffin’ & Poppin’.”

Wilbur Reynolds, who you find leading the band and blowing the sax on a few of Agee’s Krafton releases, was a fixture in L.A. recording scene for a couple of decades. He and his brother Jason Reynolds formed the aptly-named The Rocking Brothers and delivered three scorching singles that include iconic sides like wild “Night Train”-informed mambo-rocker “Rock It” and the jumpy “Playboy Hop.” He also went on to release a few exquisitely cooking later soul workouts that are definitely worth a turn: the B3-crazy rendering of Sam and Dave’s “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “Who’ll Cry (In Love Affair),” and, in an atypical reversal, its instrumental version A-side “Sweet’n,” the kinetic quirky “Tenderizer,” and the feel-good mid-tempo shaker where he blows his top “Huffin’ & Poppin’.”– An mp3 extracted from a 1970 Johnny Otis Show on Pasadena’s KPPC where Frank Zappa and Shuggie Otis back Ray Agee live in the studio on “Leave Me Alone.” The banter includes Zappa’s admission that Agee’s “Wobble-Oo” was the first record he ever stole…

– There’s sadly no in-depth Ray Agee resource online but here’s his “Big Book of the Blues” entry from the Alabama Music Office

Other Ray Agee original 45s spun at NY Night Train Soul Clap and Dance-Off:

– Leave Me Alone (Celeste, 1960)

– Your Precious Love (Celeste, 1960)

– The Wobble-Oo (Tridelt, 1962)

– Hard Working Man (Jewel, 1965)

432. Jimmy Vick And The Victors “Take A Trip” (Cherry, 1963)

You may know this Action Pat spin from King Khan and The Shrines’ frantic 2004 interpretation or its appearance on at least eight compilations. The first release on Hartford’s Cherry imprint, backed with its deep pleading flip “I Need Someone,” glimmers as the lone surviving artifact proving the uncommon excellence of this early soul aggregation. From its gospel-testifying intro to its spine-tingling conclusion, this sweaty ride is everything! The lo-fi recording, screaming vocals, cool bass break, wild guitar noodles, and raw exuberance was exactly I was looking for when it never left my record box during a good chunk of the Soul Clap and Dance-Off’s early Glasslands era. Take a trip with Jimmy Vick around the world!

You may know this Action Pat spin from King Khan and The Shrines’ frantic 2004 interpretation or its appearance on at least eight compilations. The first release on Hartford’s Cherry imprint, backed with its deep pleading flip “I Need Someone,” glimmers as the lone surviving artifact proving the uncommon excellence of this early soul aggregation. From its gospel-testifying intro to its spine-tingling conclusion, this sweaty ride is everything! The lo-fi recording, screaming vocals, cool bass break, wild guitar noodles, and raw exuberance was exactly I was looking for when it never left my record box during a good chunk of the Soul Clap and Dance-Off’s early Glasslands era. Take a trip with Jimmy Vick around the world!A Sept 21, 1963 issue of “Billboard” announcing the debut of Cherry Records describes Jimmy Vick and the Victors as “a group that has been playing in nightclubs around New England.” A “Soul Source” piece about their teenage bassist Billy Nichols explains that when Hartford’s Chime Recording Studio cut the Victors that summer for their new Cherry imprint, they didn’t yet have either the connections or expertise to market their first single beyond the area. Outside of rotation on faraway Meridian, Mississippi’s WALT, the record flopped and the band broke up by November. But the double flame they left etched into these grooves will forever burn bright!

While I have no idea what happened to the rest of the gang, Billy Nichols went on to be an unsung soul journeyman, leading the bands of Marvin Gaye and Billy Stewart, writing hits like B.T. Express’ “Do It (Til You’re Satisfied)” and Millie Jackson’s “Ask Me What You Want,” playing guitar with Pretty Purdie Playboys and Roy Ayers Ubiquity, and producing two of the most important and best seminal Hip Hop singles: Jimmy Spicer’s “The Adventures of Super Rhymes” on Dazz and Count Coolout’s “Rhythm Rap Rock” on his own Boss Records. Also check out his only ’60s record, the funky soul explosion that is 1969’s “Shake A Leg” on Sue.

– Here’s Soul Source’s comprehensive Billy Nichols piece:

433. Dino & The Dell – Tones “Sticks And Stones” (Cobra, 1966)

Jerry Lee Lewis, Jackie Shane, The Zombies, and almost any other act worth a darn in the ‘60s took a stab at Ray Charles’ #2 1960 R&B hit “Sticks and Stones.” Really anyone you can think of… Give me a name… The Beatles? Oh yeah! Of course they also did it! And while there are so many killer versions, and Titus Turner’s composition has been so easily adaptable to a wide array of voices and genres, there’s a good reason I included Dino & The Dell – Tones’ take on this standard on both my very first soul mix ever and the Norton Records’ “Souvenirs of the Soul Clap Vol 2” LP. This is the one that’s got it all! Raw immediacy, garagey production, the unmistakable lively San Antonio horn harmonies, the hard fast swingin’ beat way up in the mix, blazing Tex-Mex organ runs, and the incredible soulful vocals of the legendary Dimas Garza! While this 45 isn’t the best general representation of the stellar ‘60s Westside sound (see my piece on Rudy Tee and The Reno Bops) or the supremely passionate and often velvety ballad style Garza’s most famous for (listen to his masterpiece, a record I’ve never been able to find, “Don’t Leave Me Baby”), “Sticks and Stones” is an excellent example of how these bands sounded when they really turned up the heat in the rockin’ rhythm and blues style.

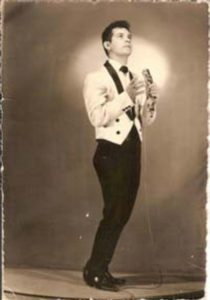

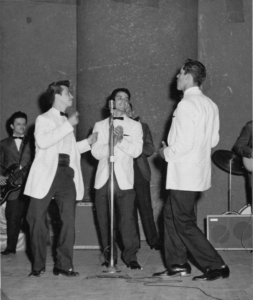

Jerry Lee Lewis, Jackie Shane, The Zombies, and almost any other act worth a darn in the ‘60s took a stab at Ray Charles’ #2 1960 R&B hit “Sticks and Stones.” Really anyone you can think of… Give me a name… The Beatles? Oh yeah! Of course they also did it! And while there are so many killer versions, and Titus Turner’s composition has been so easily adaptable to a wide array of voices and genres, there’s a good reason I included Dino & The Dell – Tones’ take on this standard on both my very first soul mix ever and the Norton Records’ “Souvenirs of the Soul Clap Vol 2” LP. This is the one that’s got it all! Raw immediacy, garagey production, the unmistakable lively San Antonio horn harmonies, the hard fast swingin’ beat way up in the mix, blazing Tex-Mex organ runs, and the incredible soulful vocals of the legendary Dimas Garza! While this 45 isn’t the best general representation of the stellar ‘60s Westside sound (see my piece on Rudy Tee and The Reno Bops) or the supremely passionate and often velvety ballad style Garza’s most famous for (listen to his masterpiece, a record I’ve never been able to find, “Don’t Leave Me Baby”), “Sticks and Stones” is an excellent example of how these bands sounded when they really turned up the heat in the rockin’ rhythm and blues style.  Dino & the Dell-Tones, who also recorded as Dino Y Los Dell-Tones, Dino Bazan & the Dell-Tones, were Westside sound hero Dimas Garza’s band before and after his historic stint in The Royal Jesters. It’s hard to overestimate Garza’s importance to Chicano Soul sub-genre. He was much more than a charismatic entertainer with matinee idol looks and miles of style, he possessed one of the most emotive versatile voices anywhere and wrote most of his own songs. From the ’50s Harlem Records doo wop of his first band The Lyrics then Dino & the Dell-Tones and The Royal Jesters, all the way through his solo releases as Dimas, Dimas III, and, by the ’80s, simply Dimas Garza, he was a massive cultural force in San Antonio’s fertile music scene.

Dino & the Dell-Tones, who also recorded as Dino Y Los Dell-Tones, Dino Bazan & the Dell-Tones, were Westside sound hero Dimas Garza’s band before and after his historic stint in The Royal Jesters. It’s hard to overestimate Garza’s importance to Chicano Soul sub-genre. He was much more than a charismatic entertainer with matinee idol looks and miles of style, he possessed one of the most emotive versatile voices anywhere and wrote most of his own songs. From the ’50s Harlem Records doo wop of his first band The Lyrics then Dino & the Dell-Tones and The Royal Jesters, all the way through his solo releases as Dimas, Dimas III, and, by the ’80s, simply Dimas Garza, he was a massive cultural force in San Antonio’s fertile music scene. The Dell-Tones, not to be confused with one of the earliest all-female vocal R&B groups, Della Simpson’s post-Enchanters aggregation The Delltones, also had a couple of records alone and a couple more as J. Jay & The Dell-Tones. Their amazing guitarist Victor Montez was the brother of The Sunglows’ Vincent Chente Montez. The organist and bandleader Johnny Zaragoza continued to play keys, write and produce after the Dell-Tones – getting production credits for six Sunny and the Sunliners 70s and 80s LPs. He also has a credit as the Sunliners manager on a record and Fusion Magazine states that he ran the super-cool Key Loc Records with Sunny Ozuna. Another Johnny Zaragoza detail is that he wrote a music column for San Antonio Express when he was in the Dell-Tones and I’ve included a scan of one of the articles here below.

Finally, we need to talk about the music mogul that produced and released “Sticks and Stones” and dozens upon dozens of other gems, Abe Epstein. Epstein was a musician who made his fortune in local real-estate. Since his prospects of becoming a rock star were growing dimmer every year, he got into the other end of the business and built a San Antonio recording empire that would grow throughout the ’60s to include Cobra, Dynamic, Jox, and other imprints. It was Epstine who convinced Dimas Garza to become Dino Bazan because of, in the words of Numero Group’s notes on Royal Jesters “The Westside Sound” compilation, “a strange scheme to make him appear like an Italian singer because Latino singers weren’t marketable nationally at that time.” While the twisted logic behind this decision more than hints at ’60s American record industry and society’s racism and xenophobia, it also speaks volumes about why so many of Epstein’s deserving artists didn’t get their due in the broader culture… Until now! Forever, as in the ’60s, the name Dimas Garza will loom much larger than the pseudonym Dino Bazan.

Finally, we need to talk about the music mogul that produced and released “Sticks and Stones” and dozens upon dozens of other gems, Abe Epstein. Epstein was a musician who made his fortune in local real-estate. Since his prospects of becoming a rock star were growing dimmer every year, he got into the other end of the business and built a San Antonio recording empire that would grow throughout the ’60s to include Cobra, Dynamic, Jox, and other imprints. It was Epstine who convinced Dimas Garza to become Dino Bazan because of, in the words of Numero Group’s notes on Royal Jesters “The Westside Sound” compilation, “a strange scheme to make him appear like an Italian singer because Latino singers weren’t marketable nationally at that time.” While the twisted logic behind this decision more than hints at ’60s American record industry and society’s racism and xenophobia, it also speaks volumes about why so many of Epstein’s deserving artists didn’t get their due in the broader culture… Until now! Forever, as in the ’60s, the name Dimas Garza will loom much larger than the pseudonym Dino Bazan.

– Take a look at this a historical artifact on the right capturing a moment in Westside Sound history, check out The Dell-Tones’ Johnny Zaragoza’s April 18, 1965 column “Spotlight On Teen Dance Bands” from San Antonio Express

– Read this biographical Dimas Garza obituary in LatinoLA.com

434. Betty Boothe “Just A Little Bit of True Love” (Enjoy, 1962)

Explosive early NYC soul by an unknown singer turning up the heat while a sharp-as-knives band, whirling by at breakneck speed, pulls out all the stops. Though Enjoy Records’ Danny Robinson told “Cash Box” (Nov, 1962) they were rushing out four new singles, including this one, “hoping for the same chart-rising results he’s experiencing with Les Cooper’s ‘Wiggle Wobble’,” its curious the seventh of the hundreds of Enjoy Records releases only existed as a DJ promo. The A-Side, the solid piano-driven ballad “I’m The One Who Needs You,” has a similar feel to the kind of gospel-inflected material Aretha Franklin was releasing on Columbia around this point. It’s also not too far off from the tone of Boothe’s only other known single on Falew a couple of years later. These other three sides don’t even hint at either the power or general aesthetic of hard driving “Just A Little Bit of True Love.” From her dangerous vocals to the velocity of the band’s proto-funk geometry, everyone involved sounds like they dropped into the session from an entirely different planet. Emboldened by the wild success of Enjoy Records’ debut release a few months prior, King Curtis’ R&B chart-topping Pop-crossover smash “Soul Twist,” the Robinson brothers’ studio sessions from the period were recorded with the crème de la crème of NYC studio players. The east coast version of the Wrecking Crew appearing on Enjoy releases included heavy hitters like Curtis, Noble Watts, Al Casey, Jimmy Lewis, Ray Lucas, etc etc etc. While this record has a murky history, or rather no history, the quality of the musicianship on this track is no accident. Despite its many obvious merits, Betty Boothe’s first record remains relatively unknown and uncompiled. Let’s give it some love!

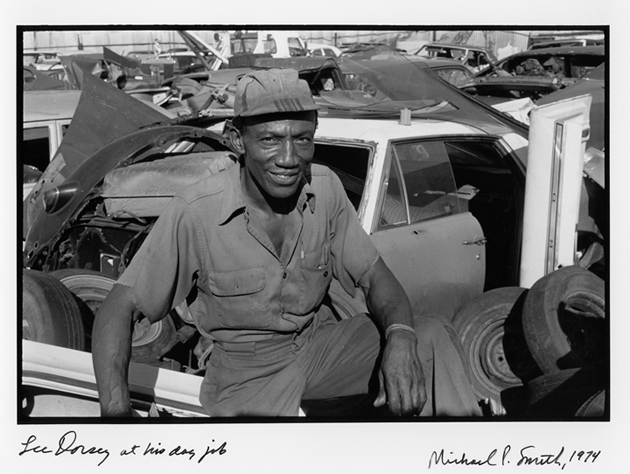

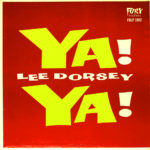

Between Fury, Fire, Robin/Red Robin, Whirlin’ Disk, Everlast, and Enjoy, the sheer quantity and quality of Bobby Robinson’s labels’ supreme blues, rhythm and blues, vocal group, and early soul classics boggles the mind! It’s even more difficult to fathom that, like Paul Winley’s Winley Records, or Jack Taylor’s Tay-Ster, Enjoy was still kickin’ into the Hip Hop era – and in Enjoy’s case leading the way with a slew of Hip Hop’s first releases – game-changing platters by Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, Funky Four Plus One More, the Treacherous Three, Enjoy’s brilliant drummer and house band leader Pumpkin, and Robinson’s nephew Spoonie Gee. I wouldn’t hesitate for a second to say that one of one of my favorite 60s labels is also my hands-down my favorite early Hip Hop imprint. Bobby Robinson, both alone and with his brother, the aforementioned Danny Robinson, wasn’t just a record man but also a hands-on visionary producer. And if I had to find a common thread between his first hit Champion Jack Dupree’s 1953 “Shake Baby Shake” on Red Robin, his most famous hits Wilburt Harrison’s “Kansas City” and Lee Dorsey “Ya Ya,” and his early Hip Hop singles, I’d say it’d be impassioned performances through elegant presentation – Robinson’s straightforward approach didn’t let an ounce of B.S. get in the way between the singer, the song, and the listener.

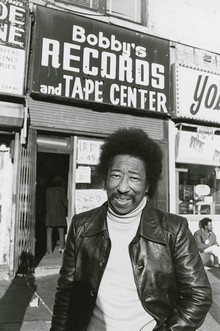

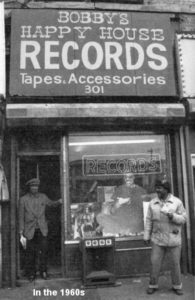

Between Fury, Fire, Robin/Red Robin, Whirlin’ Disk, Everlast, and Enjoy, the sheer quantity and quality of Bobby Robinson’s labels’ supreme blues, rhythm and blues, vocal group, and early soul classics boggles the mind! It’s even more difficult to fathom that, like Paul Winley’s Winley Records, or Jack Taylor’s Tay-Ster, Enjoy was still kickin’ into the Hip Hop era – and in Enjoy’s case leading the way with a slew of Hip Hop’s first releases – game-changing platters by Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, Funky Four Plus One More, the Treacherous Three, Enjoy’s brilliant drummer and house band leader Pumpkin, and Robinson’s nephew Spoonie Gee. I wouldn’t hesitate for a second to say that one of one of my favorite 60s labels is also my hands-down my favorite early Hip Hop imprint. Bobby Robinson, both alone and with his brother, the aforementioned Danny Robinson, wasn’t just a record man but also a hands-on visionary producer. And if I had to find a common thread between his first hit Champion Jack Dupree’s 1953 “Shake Baby Shake” on Red Robin, his most famous hits Wilburt Harrison’s “Kansas City” and Lee Dorsey “Ya Ya,” and his early Hip Hop singles, I’d say it’d be impassioned performances through elegant presentation – Robinson’s straightforward approach didn’t let an ounce of B.S. get in the way between the singer, the song, and the listener. Bobby Robinson started in the music biz in 1946 by opening one of the first Black-owned record stores and becoming arguably the first Black business owner on 125th street (according to the NY Times). Bobby’s Happy House (originally Bobby’s Record Shop) remained a Harlem fixture into the 21st Century. He got to know the parade of artists playing a few feet away at The Apollo and set up his Robin imprint to record them. From these humble beginnings the enterprise steadily grew each year as it bloomed into one of the mightiest catalogues in music history. A super-snazzy dresser with a majestic long white mane, Bobby Robinson was still lording over his record store when was evicted in 2008. Its hard to imagine that less than a couple of decades ago in NYC, if you were in the mood to meet a towering cultural giant straight outta the history books, you could find the likes of Bobby Robinson and Coxone Dodd humbly behind the counter of their shops.

Bobby Robinson started in the music biz in 1946 by opening one of the first Black-owned record stores and becoming arguably the first Black business owner on 125th street (according to the NY Times). Bobby’s Happy House (originally Bobby’s Record Shop) remained a Harlem fixture into the 21st Century. He got to know the parade of artists playing a few feet away at The Apollo and set up his Robin imprint to record them. From these humble beginnings the enterprise steadily grew each year as it bloomed into one of the mightiest catalogues in music history. A super-snazzy dresser with a majestic long white mane, Bobby Robinson was still lording over his record store when was evicted in 2008. Its hard to imagine that less than a couple of decades ago in NYC, if you were in the mood to meet a towering cultural giant straight outta the history books, you could find the likes of Bobby Robinson and Coxone Dodd humbly behind the counter of their shops.Bobby Robinson will reappear again a few songs down this list when we encounter Lee Dorsey….

– Blues Unlimited radio show about Bobby Robinson that could be accurately described as two hours of the best music of all-time with some facts

– A 1993 Terry Gross’ NPR Fresh Air episode dedicated to Bobby Robinson

– A 2007 NY Times article from when Bobby Robinson and his Happy House were about to be displaced from gentrifying Harlem

– Andy Shwartz’s 2011 NY Rocker exploration of the great man’s life and an account of his funeral

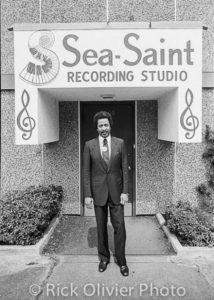

Allen Toussaint escapes the studio in 1968 to get back behind the piano! By Jonas Bernholm from his amazing “Soul Music Odyssey USA 1968”

The next three tracks are productions from the great American composer Allen Toussaint’s compelling late ‘60s mid-period in which he relentlessly experimented in the studio. While Toussaint is a virtuosic pianist with a honey voice and one of our most prolific and enduring songwriters, his most valuable instrument was the way in which he assembled and wove New Orleans’ rich musical resources into bold artistic statements that were rooted in local musical traditions but still uniquely contemporary. By the age of 21, when the young session pianist / touring sideman ascended from audition accompanist to an all-encompassing role at Joe Banashak’s Minit Records in a matter of weeks, songs flowed out of him like the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico. He casually penned “Mother-In-Law,” “T’aint It The Truth,” “Wanted $10,000 Reward” and “Hello My Lover” for Ernie K-Doe all in one day. The unprecedented string of brilliant beads he wrote, produced, arranged, and/or played on (typically all four!) in his earthquake of an early period, so many of the Ernie K-Doe, Irma Thomas, Chris Kenner, Jessie Hill, Benny Spellmen, and Aaron Neville classics we still listen to today, terminated when he was drafted into the army in 1963. Though he returned periodically on leave to quickly cut the whipped cream of his Alon era, he was discharged into an entirely different musical landscape in 1965. A collaboration with former Bobby Robinson A&R and promotions go-getter Marshall Sehorn in rejuvenating the career of another down on his luck Big Easy legend Lee Dorsey sparked Toussaint’s next creative explosion. The deal that they made with Bell Records subsidiary Amy for Dorsey, and the releases from their partnerships like the Sansu, Tou-Sea, and Deesu labels, offered the visionary producer the materials to create an entire new museum of masterpieces.

The next three tracks are productions from the great American composer Allen Toussaint’s compelling late ‘60s mid-period in which he relentlessly experimented in the studio. While Toussaint is a virtuosic pianist with a honey voice and one of our most prolific and enduring songwriters, his most valuable instrument was the way in which he assembled and wove New Orleans’ rich musical resources into bold artistic statements that were rooted in local musical traditions but still uniquely contemporary. By the age of 21, when the young session pianist / touring sideman ascended from audition accompanist to an all-encompassing role at Joe Banashak’s Minit Records in a matter of weeks, songs flowed out of him like the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico. He casually penned “Mother-In-Law,” “T’aint It The Truth,” “Wanted $10,000 Reward” and “Hello My Lover” for Ernie K-Doe all in one day. The unprecedented string of brilliant beads he wrote, produced, arranged, and/or played on (typically all four!) in his earthquake of an early period, so many of the Ernie K-Doe, Irma Thomas, Chris Kenner, Jessie Hill, Benny Spellmen, and Aaron Neville classics we still listen to today, terminated when he was drafted into the army in 1963. Though he returned periodically on leave to quickly cut the whipped cream of his Alon era, he was discharged into an entirely different musical landscape in 1965. A collaboration with former Bobby Robinson A&R and promotions go-getter Marshall Sehorn in rejuvenating the career of another down on his luck Big Easy legend Lee Dorsey sparked Toussaint’s next creative explosion. The deal that they made with Bell Records subsidiary Amy for Dorsey, and the releases from their partnerships like the Sansu, Tou-Sea, and Deesu labels, offered the visionary producer the materials to create an entire new museum of masterpieces. The three lesser-known sides below, all as deserving of a place in his vast cannon, like his later icon “Southern Nights,” exemplify an American pastoral bent in some of his work. From the protagonist of “In My Corner” getting his food from a crawfish hole, to “Do Me Like You Do Me’s” banjo sounds that ease their way up to dominance in the mix, to “A Lover Was Born’s” rustic farm-based lyrics and rhythm, the urbane Toussaint employs rural themes and signifiers to his artful compositions in a similar fashion that Aaron Copland employs them to his modernist vernacular orchestral works like “Appalachian Spring.” While many of these more subtle tracks found their way into my sets from the beginning, they took on a bigger importance to my ears and brain during Covid when I had more time to pay attention to the subtleties that gradually emerge as Toussaints musical narratives unfold.

– 2015 Quietus Interview

– 2012 Something Else Interview

– 2015 NPR Fresh Air Interview

435. Ray Algere “In My Corner” (Tou-Sea, 1967)