|

|

|||||||||||

| June 2006: SPOTLIGHT ON... NOTEKILLERS

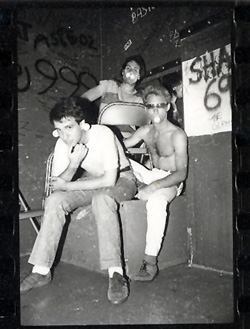

Zoom in a bit closer on the faces and the narrative becomes almost as fascinating as the music - particularly because the members of the vigorous instrumental power-trio are all fifty-somethings. Between 1977 and 1981, Notekillers fashioned music light-years in the future, left a lone document of their subterranean existence, and resurfaced a quarter-century later after learning that not all of the five-hundred copies of the record had fallen on deaf ears – informing contemporary music in general from deep down below. While Thurston Moore’s advocacy, and the resulting excavation of this brilliant obscurity deeply buried by time, makes for interesting copy, the highlight of this saga is the triumphant punch line: after a good dusting-off, the artifact that was revealed, more than merely intact, emitted a blast of sound unprecedented for a reunion band and unequalled anywhere on the planet. A couple of adolescents playing "jammy/jazzy/Latinish rock" inspired by Love and Spirit in the coffeehouses of Philadelphia, guitarist David First and drummer Barry Halkin initiated their live performance career together in the late-1960s. By 1969 when they were students at Philadelphia’s Northeast High, Steven Bilenky joined them in a combo called Dead Cheese. After high school First gravitated towards avant jazz, joining Cecil Taylor from 1973 to 1974, abandoning that genre and moving towards new minimalist music, experimenting with a Buchla modular synthesizer in the mid-1970s in Princeton, and finally, returning to Philadelphia and his old partner in crime Halkin. The two rented a basement and went about creating what they dubbed "free rock” (a term currently thrown rather loosely around the indie world). By the time their high school band mate Bilenky fell into the mix in 1977, they were christened Notekillers. Though the trio was inspired by the CBGB bands of the mid-1970s, and they were quickly regular performers in Philadelphia’s first punk clubs, Notekillers drew inspiration from a variety of other sources outside of the punk sphere – particularly jazz and various edges of the avant-garde. In addition to a more diverse, virtuosic, and generally ambitious approach to punk, the band’s reaction to the mainstream rock of the day was also distinct from their contemporaries in that it remained exclusively instrumental. First told Philadelphia’s City Paper’ A.D. Amorosi:

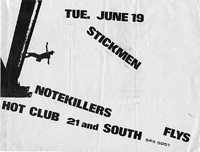

Slowly burning out, by 1980 the band decided that they were too weird for Philly. They chose to cut a record, take a break from local gigging, and see how their music fared in the outside world. Setting up a four-track in the basement of Bilenky’s father’s beauty parlor, Beauty on a Budget, Notekillers recorded “The Zipper” backed by “Clockwise” 7”. The record that indirectly prompted their return a quarter-century later, “The Zipper,” a song you won’t believe was committed to tape in 1980, is one of the more sublime cuts you’re likely to hear in your lifetime. The track’s pulsating intensity, jagged rhythm, and jazzy harmonics, light years beyond any British post-punk entity, resembles a more musically accomplished and ambitious, less-bluesy instrumental take on what the Minutemen were attempting at the same time. It also may remind you a bit of the dozens of trios who added a proggy edge to the Minutemen’s aesthetic later in the decade and into the early 1990s. And the “Clockwise” flipside, another fine composition, sounds like a dangerously armed yet quirky Television. Ed Bahlman, boss of the important and amazing 99 Records label and store, was impressed with the recording and brought Notekillers to New York for gigs at CB’s, Hurrah’s, and Maxwell’s. They even played a show with Glenn Branca. By the time they were finally picking up a bit of momentum, the trio was already exhausted from years of constant unrewarded effort. In 1981 the members went their separate ways, leaving a dazzling second single, a burlesque of The Ventures' surf icon “Walk Don’t Run,” entitled “Run Don’t Stop,” unreleased. Halkin abandoned the music business for years, becoming an architectural photographer. A few years ago he picked up his sticks once more to join the soul classics group More Soul. Bilenky, who did time in the Baal Shem Tov Band, a Hasidic rock unit, found success with his own Olney custom bicycle shop, Bilenky Cycle Works – and his business’ official band. First was the only one who consistently pursued a career in music – changing his name, moving to New York, and becoming an internationally respected avant composer and guitarist. Notekillers’ unlikely reunion began when First picked up a call from Halkin in 2002. A friend had informed Halkin that Thurston Moore included the band’s “The Zipper” on his fantasy mixtape in Mojo. Describing the record as “mind-blowing,” Moore knew nothing more about the band other than that they were from Philly, concluding, “We’ve got to find out who these guys are.” Moore has since cited the single, with its collision of punk energy and avant jazz aesthetics, as a significant influence on Lee Ranaldo, Kim Gordon, and himself. “Their songs are really concise but they were referencing all these things they were turned on by, from Albert Ayler to hard rock, which at the time, nobody else was. The music is way ahead of its time."

In an uncommon regrouping that includes all of the original members, Notekillers have been leaving jaws on the floor since 2004 - their old material coming off as fresh in today as twenty-five years ago, and the new ones pushing forward into the unknown. More than a curiosity, Notekillers are the sonic and physical personification of time unfolding upon itself… And easily as vital as any contemporary band out there.

Continue

to "Notekillers - On Returning: A Conversation With David First"

|

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

First,

who both shared past bills with various Sonic Youths and played

on a record with Moore, emailed his fellow guitarist: “hey,

that was me.” Soon he was sorting through boxes of demos,

live tapes, and rehearsals for the first full-length Notekillers

album, a compilation released on Moore’s Ecstatic Peace imprint.

He next went about reassembling the band. Stephen Bilenky was the

first to agree and Halkin, who took a little more convincing, finally

gave in.

First,

who both shared past bills with various Sonic Youths and played

on a record with Moore, emailed his fellow guitarist: “hey,

that was me.” Soon he was sorting through boxes of demos,

live tapes, and rehearsals for the first full-length Notekillers

album, a compilation released on Moore’s Ecstatic Peace imprint.

He next went about reassembling the band. Stephen Bilenky was the

first to agree and Halkin, who took a little more convincing, finally

gave in.