December

1 , 2005

Kid Congo Powers

Issue, Pt. 1

Blood on the Wall

Psychic Ills

Morning Theft

Maxwell's

12/02

***

Cannibal

Ox

C-Rayz Walz

The Reavers

Bowery Ballroom

12/04

***

Lucky

Dragons

Telepathe

Growing

Sleepy Doug Shaw

Tonic

***

The

Deadly Snakes

Mercury Lounge 12/07

Piano's 12/08

Maxwell's 12/10

|

||

| home | table of contents |feature | record reviews | live shows | news | events |archive | record label | links | contact |

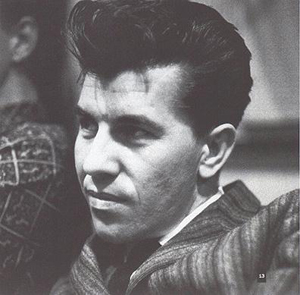

Mr. Guitar's City After Dark

Last

Saturday I found a rumor in my email box that guitar legend Link Wray

had passed away. After searching for a couple of hours, all I could

find was a Spanish obituary on myspace and a RIP posting from Robert

Gordon’s webmaster on a Link Wray site. So it wasn’t until

Monday, three days after his death, that it was confirmed and the press

picked it up. The late and hasty obituaries all talk about his invention

of the power chord and guitar distortion, his influence on 1960s British

rockers, and his hard rock legacy. While these are all important aspects

of Link Wray’s musical legacy, much of the rhetoric is simplified,

inaccurate, and weighs insufficiently on his artistic, musical, and

stylistic accomplishments.

Last

Saturday I found a rumor in my email box that guitar legend Link Wray

had passed away. After searching for a couple of hours, all I could

find was a Spanish obituary on myspace and a RIP posting from Robert

Gordon’s webmaster on a Link Wray site. So it wasn’t until

Monday, three days after his death, that it was confirmed and the press

picked it up. The late and hasty obituaries all talk about his invention

of the power chord and guitar distortion, his influence on 1960s British

rockers, and his hard rock legacy. While these are all important aspects

of Link Wray’s musical legacy, much of the rhetoric is simplified,

inaccurate, and weighs insufficiently on his artistic, musical, and

stylistic accomplishments.

Before I proceed, Link Wray did not invent the power chord. The power chord is a combination of guitar notes, typically in the major scale, which involves the root note played on one of the lowest two strings as well as the next octave higher. It can be found in all kinds of musical forms dating back long before the electric guitar. Link Wray’s distinction was not in his creation of that type of chording but his employment of it. Instead of using it primarily for background rhythmic purposes, Wray was perhaps the first notable instrumental rock musician to feature the power chord prominently as the basis of songs as opposed to the typical single string melodic line – as exemplified in “Rumble.” Also, in most of the Link Wray singles that followed, simple single-string melodies tended to drive the song instead of the “Rumble” chord-basis. Perhaps due to a lack of decent source material on Wray, this, along with most of the other information from the obituaries seem to come from Cub Koda’s AllMusicGuide statement (“Link Wray invented the power chord”) which was not intended to be taken literally.

In

regards to distortion, the sound of a guitar overdriving an amplifier

has been around since the creation of the electric guitar – and,

on recordings, can be found as far back as the 1930s in swing and particularly

western swing bands. While fuzz and feedback were arguably technical

glitches that sometimes could not be prevented in the early days of

electric instruments, beginning the late 1940s, particularly in the

Chicago blues, the conscious aesthetic decision to employ distorted

guitar sounds on recordings became commonplace. Wray did however create

and popularize a unique overdriven guitar sound through amplification

experiments such as punching little pencil-holes in speakers.

In

regards to distortion, the sound of a guitar overdriving an amplifier

has been around since the creation of the electric guitar – and,

on recordings, can be found as far back as the 1930s in swing and particularly

western swing bands. While fuzz and feedback were arguably technical

glitches that sometimes could not be prevented in the early days of

electric instruments, beginning the late 1940s, particularly in the

Chicago blues, the conscious aesthetic decision to employ distorted

guitar sounds on recordings became commonplace. Wray did however create

and popularize a unique overdriven guitar sound through amplification

experiments such as punching little pencil-holes in speakers.

Wray was much more than in inventor, he was an innovator. His application of recent technology, musical techniques, and social phenomena jump-started a few strains in contemporary global popular music and culture in both style and substance. The evidence of his impact is vast – stretching across a number of musical genres, artistic media, and geographical boundaries.

In terms of influence, while Wray’s impact on Pete Townsend, Neil Young, or other sixties guitar heroes is certainly significant, and the fact that hard rock, metal, and punk took a lot of Wray’s innovations from other sources down the line, he was more than a once or twice-removed influence contemporary music. A good chunk of bands “left of the dial” in the last three decades since he informed the sixties garage and British invasion sounds have been directly informed by Wray. Contemporary bands that cover his songs include Americanos like The Cramps, The Monomen, Southern Culture on the Skids, the Flat Duo Jets, Cash Money, Los Straight Jackets, and even the God Bullies, Canadians like Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet, Brits like Billy Childish, solo and with The Milkshakes and Thee Headcoats, and Japanese like Supersnazz, and Guitar Wolf. Guitar Wolf should receive special attention for appropriating Wray’s sound, look, attitude, and overall aesthetic. Another fact that warrants mention is that in Wray’s heyday he directly anticipated and influenced the emerging surf instrumental genre. The Ventures, the Tornadoes, and the Surfaris all appeared after Wray and recorded his songs. Others, like the Trashmen, borrowed a bit more than merely his songs.

Wray’s presence within and influence on contemporary culture was not limited to music. His roomy, melodramatic, and, frankly, cinematic sound made his songs strong candidates for motion picture soundtracks. John Waters led the pack featuring “Rumble’s” B-side, “The Swag,” in Pink Flamingos (1972). “Jack the Ripper” shows up in the 1983 American remake of Breathless and in Desperado (1996). “Rumble” appears in a number of films including Streets of Fire (1984), Independence Day (1996), Blow, and Pulp Fiction (which also contains Wray’s “Ace of Spades”). “Commanche” appears in 12 Monkeys. And the list goes on. So, even though “Rumble” doesn’t show up much on oldies radio, Link Wray has found other routes into the public subconscious.

Link Wray’s sound, style, and career stood at an intersection of rock and roll, the rise of the guitar instrumental, the cult of the juvenile delinquent, and modernity in general. Finding popularity at the tail-end of the rock n’roll era, Ray created a sound that was much more gritty, elegant, and self-consciously tough than anything that had come before or since. The imagery evoked not only by the music, but also by song title s like “Jack the Ripper,” “The Black Widow,” “The Shadow Knows,” or, of course “Rumble,” combined with Ray’s black leather and sunglasses attire, suggested the violence lurking beneath the urban night. While Link Wray himself was a rather gentle straight-laced Christian, his instrumental noirs celebrated the illicit activities of the alleys and back rooms of the American wrong side of town.

Link

Wray also fits in perfectly with the minimalist aesthetics of 1950s

art, architecture, design, and, of course, popular music. Just as Miles

Davis didn’t have the technical prowess of Dizzy Gillespie and

turned it into a strength with the creation of “cool” via

space and pacing, when Miles was later paring away the layers in during

his elegant modal period, Wray created “Rumble” with the

knowledge that he didn’t have the chops of Tal Farlow or Chet

Atkins - he set out to create something altogether different. Duane

Eddy, who became a sensation in 1958 with ridiculously simple guitar

lines whose appeal lay in the well-reverb sound created by Lee Hazelwood

in grain silos, not only opened the market for simple guitar instrumentals

but also offered a bit of a blueprint for Wray’s new stylistic

shift. Wray definitely cranked up the reverb and tremolo on his tracks

and, on “Rawhide’s” flipside, “Dixie-Doodle,”

does an all-out Eddy impersonation. So like Eddy, he found extremely

basic melodies, and filtered them through an extremely stylized sound.

While Eddy’s distinct feature was reverb, Wray’s was distortion.

Additionally, Eddy’s popular success as a guitar instrumentalist

helped create and define the economic market in which Wray’s instrumentals

were produced.

Link

Wray also fits in perfectly with the minimalist aesthetics of 1950s

art, architecture, design, and, of course, popular music. Just as Miles

Davis didn’t have the technical prowess of Dizzy Gillespie and

turned it into a strength with the creation of “cool” via

space and pacing, when Miles was later paring away the layers in during

his elegant modal period, Wray created “Rumble” with the

knowledge that he didn’t have the chops of Tal Farlow or Chet

Atkins - he set out to create something altogether different. Duane

Eddy, who became a sensation in 1958 with ridiculously simple guitar

lines whose appeal lay in the well-reverb sound created by Lee Hazelwood

in grain silos, not only opened the market for simple guitar instrumentals

but also offered a bit of a blueprint for Wray’s new stylistic

shift. Wray definitely cranked up the reverb and tremolo on his tracks

and, on “Rawhide’s” flipside, “Dixie-Doodle,”

does an all-out Eddy impersonation. So like Eddy, he found extremely

basic melodies, and filtered them through an extremely stylized sound.

While Eddy’s distinct feature was reverb, Wray’s was distortion.

Additionally, Eddy’s popular success as a guitar instrumentalist

helped create and define the economic market in which Wray’s instrumentals

were produced.

Wray is also important for his uncompromising dedication to an aesthetic. After the success of “Rumble” and “Rawhide” in 1958 and 1959 respectively, Epic decided to give him an overproduced easy listening sound on “Trail Of The Lonesome Pine” and “Golden Strings” and put him with an entire orchestra on "Danny Boy"/"Claire de Lune." Before I move on, on a side note, “Golden Strings,” often pooh-poohed by Wray fans, is actually a work of supreme beauty based on a Chopin etude. After Epic’s failure sell the white-washed Wray on these four sides, the guitarist continued on where he left off for over forty years - never straying too far from his beliefs about how a guitar should sound or be played.

Between 1960 and his brief retirement in 1966, Wray filled up a period not typically associated with raw rock and roll with some of the most raunchy sides ever produced – one of the many examples that completely disproves the popular misconception that rock’n’roll died in American in the late 1950s and was brought back by the Brits in the mid-1960s. After the fallout with Epic, Wray and his brother started their own label for three releases. At this point they were selling records out of the back of the car. One of the records, “Jack the Ripper,” was picked up by Philadelphia’s Swan label in 1963 and became Wray’s third and last charting single. Wray remained on Swan for the next few years. Though they marketed him as a surf guitarist, Swan gave Wray fairly unlimited creative freedom. This arrangement produced not only a few rough vocal numbers, but also instrumental classics like “The Black Widow” (1963), “Run Chicken Run” (1963), “The Shadow Knows” (1964), “Deuces Wild” (1964), “Branded” (1965), “The Ace of Spades” (1965) and “Fuzz” (1965). During this period Wray had his own underground following. While Wray did his share of fraternity gigs, he was a particular favorite with bikers and gamblers up and down the east coast. Wray played mostly dives, roadhouses, and casinos in the DC/Maryland area.

Frustrated

with the music business, Wray retired and settled down on his family’s

Maryland farm in the late 1960s. During his “retirement”

he recorded a few singles – a remake of “Jack the Ripper”

(1967) and three remakes of “Rumble”: “Rumble Mambo”

(1967), “Rumble ‘68 “(1968), and “Rumble ‘

69” (1969). During this period he and his brother Vernon began

assembling recording equipment at the farm and were slowly building

a body of material. Much of this was made public after his 1970 comeback

and PolyGram signing. His first album of this period, Link Wray,

is a homespun affair using all kinds of unusual tool-shed instrumentation.

While it was recorded in a homw studio in a proper building on the farm,

the label promoted it as being recorded in a chicken coop. The next

one, Be What You Want To was country themed and featured Jerry

Garcia and Commander Cody. After that Wray was once again doing what

he does best with Link Wray Rumble. Pete Townsend paid some

of his debt by writing the liner notes and names like Boz Scaggs and

Pete Escovedo also appeared. Bernie Kraus played and programmed the

moog, which put the foot that wasn’t in the past in the future.

Frustrated

with the music business, Wray retired and settled down on his family’s

Maryland farm in the late 1960s. During his “retirement”

he recorded a few singles – a remake of “Jack the Ripper”

(1967) and three remakes of “Rumble”: “Rumble Mambo”

(1967), “Rumble ‘68 “(1968), and “Rumble ‘

69” (1969). During this period he and his brother Vernon began

assembling recording equipment at the farm and were slowly building

a body of material. Much of this was made public after his 1970 comeback

and PolyGram signing. His first album of this period, Link Wray,

is a homespun affair using all kinds of unusual tool-shed instrumentation.

While it was recorded in a homw studio in a proper building on the farm,

the label promoted it as being recorded in a chicken coop. The next

one, Be What You Want To was country themed and featured Jerry

Garcia and Commander Cody. After that Wray was once again doing what

he does best with Link Wray Rumble. Pete Townsend paid some

of his debt by writing the liner notes and names like Boz Scaggs and

Pete Escovedo also appeared. Bernie Kraus played and programmed the

moog, which put the foot that wasn’t in the past in the future.

The comeback faded

and Wray disappeared once again only to resurface in the late 1970s

with CBGB regular/Tuff Darts frontman Robert Gordon for a couple of

records of retro-rockabilly, Robert Gordon With Link Wray (1977)

and Fresh Fish Special (1978). 1979 saw another Wray noir,

Bullshot, with a mix of vocal and instrumental tracks, the

best of which are Ray's tough play on "Peter Gun," "Switchblade,"

and yet another version of his own "Rawhide." He made a live

record the next year featuring session drummer Anton Fig who later found

notoriety not only for his name but as a member of Frehley’s Comet

and the David Letterman house band. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s

he continued to make occasional live or studio albums on obscure European

labels - sometimes with drum machine, sometimes with band. Because more

compilations began slowly appearing, by the point that Wray made his

comeback with Shadowman in 1997, there were a few generations

of folks ready to listen.

The recording and touring during the years between Shadowman and Wray’s death was fairly consistent and helped reinforce Wray’s legacy. Shadowman had some of his best songs. His chops were perhaps better than ever. His sound, while a bit more contemporary, was still plenty dark and dirty. His live band understood the power and restraint of the music and were much less cheesy and more rocking than say, Dick Dale’s. Wray was still wearing all-black and sunglasses and his frame remained slim - the only physical modificatios being a ponytail trailing all the way down his back, a fannypack, and a few wrinkles. It also didn't hurt that he began to finally receive the most critical acclaim of his fifty years in the biz. The interest created by Wray’s final comeback resulted in a windfall of compilations and re-releases that is certain to only increase now that he has passed away. I personally have been impatiently awaiting the release of Law of the Jungle – Swan Demo’s ’64, a collection of lost tracks recently found on a tape from the height of Wray's artistic powers.

Tirelessly painting his dark sonic cityscapes until his death, Link Wray, as always, did not go gentle.

© New York Night Train , 2005